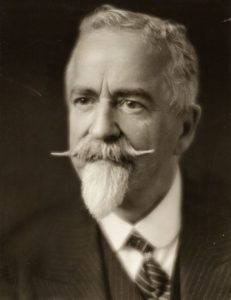

Champion of French language rights, Genest led the fight against the Ontario government’s attempt to restrict French language education in the early years of the 20th Century.

Genest lived at several addresses in Sandy Hill, including 646 Cumberland St. (before 1910), 73 Blackburn (1911 to at least 1916), 559 King Edward Ave. (1921-1923) and finally 252 Wilbrod St. (1924 – 1937).

Born in Trois-Rivières, Genest was a surveyor by profession and worked most of his life for what was then the federal Department of the Interior. But it is for his role as the chair of the Conseil des Écoles séparées d’Ottawa (CESO) between 1913 and 1930 that he is remembered today. In 1912, the Ontario Government had introduced Regulation XVII to restrict French language education in public and separate schools[1]. French schools throughout the Province refused to comply and many saw their government funding cut and their teachers suspended as a result. The French Canadian community rallied to raise money to pay teacher salaries and keep their schools open; in some cases, they opened parallel schools where the local Board of Education would not support them; they signed petitions, held demonstrations and appealed to the courts, including to the British Privy Council; they founded a newspaper to support their fight, the daily Le Droit which still publishes today. Most famously, the “dames gardiennes” – the mothers of the pupils in question – formed picket lines around several schools and threatened to stab provincial officials and policemen with their hatpins.

As chairman of the largest francophone school board in Ontario, Genest was at the centre of this fight. The CESO initially refused to implement Regulation XVII but a court injunction prevented it from paying teacher salaries as long as it maintained its refusal. The government eventually dismissed the elected CESO and appointed its own School Board. It also revoked the teaching certificates of teachers who continued to defy Regulation XVII and even threatened some with jail.

1916 marked the year of greatest confrontation. On January 4, parents and teachers seized École Guiges in Lowertown in spite of a police presence. They would guard it and other schools around the clock for a month. On February 3, having run out of money, the CESO was forced to close its 17 schools (they would remain closed for the rest of the school year). The next day, the Parliament buildings burned. This tragedy, coupled with the fear that the fire was the result of German arson, deflected public attention from the crisis in the separate school system.

In 1917, after the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London ruled that the Ontario government had erred in dissolving the school board, CESO recovered access to some of its funds and paid its teachers. This prompted an anglophone board member in May to sue Genest for paying unlicensed teachers in violation of a 1914 injunction, and to ask for both jail time for Genest and a return of the salaries that had been paid to teachers. The reason why some teachers were unlicensed, of course, was because the government had withdrawn their teaching certificate after they refused to apply Regulation XVII. These proceedings unfolded over the better part of a year against the background of the conscription crisis and a federal election, both of which raised political tensions in Ottawa to new levels. Genest did not go to jail, although his fight cost him financially. On September 21, 1918, the Ottawa Journal reported a private fundraising effort was ongoing to compensate Genest and Sir Wilfrid Laurier had contributed $100. Gradually, Ontario public opinion shifted in favour of recognizing French language rights.

The Ontario government eventually stopped enforcing Regulation XVII and recognized the right to French primary education in 1927 (the government started funding French high schools only in the 1970s) but the Regulation stayed on the books until 1944. In February 2016, a hundred years after the confrontation in front of the École Guigues, Premier Kathleen Wynne apologized in the Ontario legislature for the harm the Regulation had caused to Ontario’s francophones. Genest received many honours from the French Canadian community, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Ottawa in 1928.

At the time, Regulation XVII created enormous resentment among all French Canadians and was one of the factors nationalists cited against conscription during WW 1. They compared Ontario’s policy to Germany’s treatment of Polish teachers in occupied Silesia, where the teaching of Polish was forbidden, and argued: why fight overseas when the real battle for survival is right here at home?

[1] Regulation XVII reflected concerns from conservative protestants that the rapidly-growing francophone catholic population would not integrate properly into Ontario’s mainstream.